You would think Disney might have cornered the market on King Arthur films. The studio’s takes on Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Winnie the Pooh, and Mary Poppins are so ubiquitous they’ve overtaken the British source material in pop culture, the studio’s earliest forays into pure live-action filmmaking were made up of adaptations of British novels and legends, and Arthurian lore’s collection of kings, castles, magic, and romance seems an ideal fit for Disney at first glance. But the Matter of Britain has yet to have a movie that defines the legend for the medium of cinema in the way that, say, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) did. King Arthur adaptations have come as musicals, spoofs, low-budget trash, cult classics of debatable quality, and a string of recent efforts that just haven’t caught the public’s eye in a big enough way (best of luck to The Green Knight in that regard). And then there’s Disney’s one attempt at Arthurian legend, 1963’s The Sword in the Stone, which did less for Arthurian movies than it did for Walt Disney Animation.

It wouldn't appear that way at first glance. The Sword in the Stone isn’t the most acclaimed of Disney’s catalog. It isn’t the most popular. It wasn’t the most successful at the box office. Compared to the films produced in the 70s and 80s, the film has left a fair-sized stamp on the Disney legacy; the sword itself is a popular photo op in the theme parks, and the film’s interpretation of Merlin has gone on to a decent-sized role in the Kingdom Hearts series. And there are fans; my father’s one of them and I was one of them as a kid, though these days I find the film meandering and uneven. But whatever the individual members of my family think, The Sword in the Stone has never been the first thing that comes to most minds when you mention Disney animation or King Arthur.

Well, that may only be true for films, as far as King Arthur is concerned. For generations of readers, The Sword in the Stone may be among the first titles they think of for Arthurian lore. It’s the first book of The Once and Future King, T.H. White’s tetralogy that reshapes the medieval Le Morte d’Arthur into a 20th-century reflection on morality, leadership, and war. The Sword in the Stone depicts Arthur’s childhood as the ward to a knight, unknowing of his lineage or destiny, given a magical education by the eccentric wizard Merlyn (and that is how it’s spelled in the text). The second book, The Queen of Air and Darkness, contrasts the rise of Arthur as a young king and his attempts to apply Merlyn’s lessons to his rule with the plight of his unknown nephews, who grow up at the mercy of their unstable, scheming mother Morgause. Arthur continues to wrestle with how to be a good man and king in The Ill-Made Knight, but the third book is chiefly concerned with the doomed romance between Queen Guinevere and an insecure, disfigured Sir Lancelot. Finally, The Candle in the Wind brings the tragedy to a close as Arthur’s bastard son Mordred turns the queen’s affair against them, and the tetralogy ends with Arthur reflecting one last time on his youth with Merlyn before riding out to his death. No less an expert on fantasy than George R. R. Martin has called The Once and Future King “the definitive modern treatment of the Matter of Britain” and advocated for a multi-part film adaptation a la The Lord of the Rings.

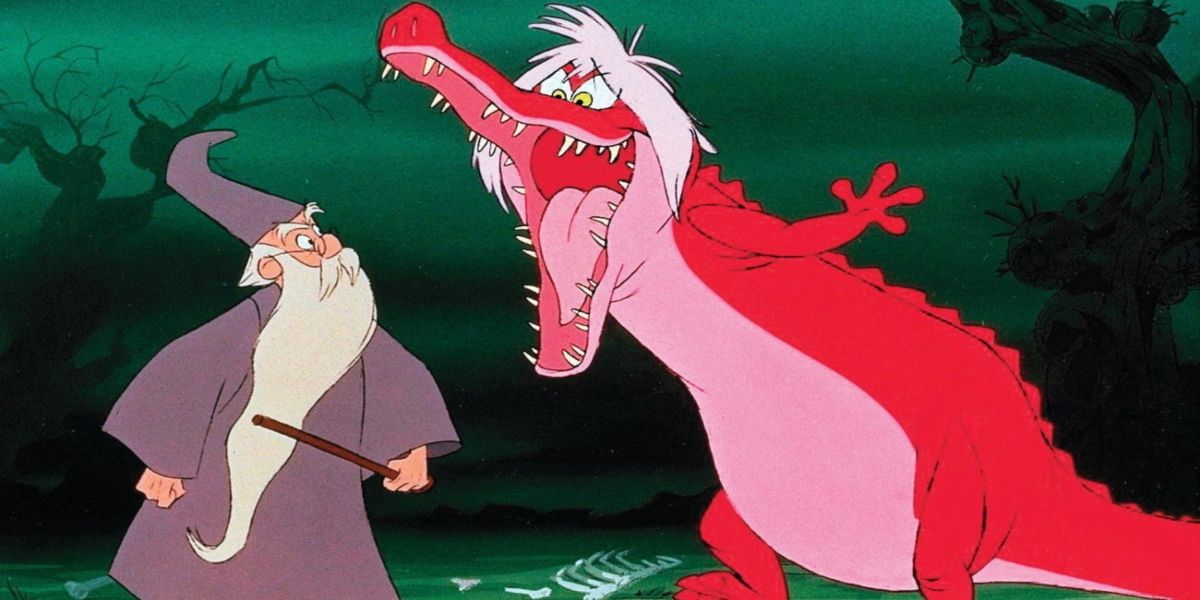

Unlike J.R.R. Tolkien, however, White didn’t set out to tell an epic. When he first published The Sword in the Stone in 1938, it was a standalone tale meant for children, a fantasy of Merrie Olde England that bordered on parody. Merlyn in White’s telling ages backward through time, making him cognizant of the future but easily confused between what has happened and what will happen. Anachronisms abound as Merlyn blusters about locomotives and swears he’ll be blown to Bermuda. Meanwhile, young Arthur encounters fairies, Robin Hood, and the mad Madame Mim before getting anywhere near swords or stones. You won’t find this edition in collections of The Once and Future King; White heavily revised The Sword in the Stone once he decided to expand it into a tetralogy, pulling it in a more philosophical direction that would tie into the later books. It remains the most lighthearted of the four, but it should tell you something about how different they are when the magical duel between Merlyn and Mim is the centerpiece of the first edition, while a lesson taught by geese about the illusion of national borders fading away when viewed from above is the centerpiece of the revised story.

But those revisions were decades away in 1938. The Sword in the Stone was still a work of whimsy when Walt Disney took a shine to it. In the wake of his success with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, Walt was keen to line up as many feature animated projects as he could, and he acquired the rights to White’s novel in 1939. That was about as far as any film version went for a few years. Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi superseded it in going into production. Their underperformance at the box office, World War II, and a bitter animators’ strike, all in the span of three years, derailed Walt’s ambitions and left him uncertain and demoralized. Walt Disney Productions would limp through the 1940s on a series of package features and live-action/animated hybrids. The Sword in the Stone, like many a potential movie Walt had considered, was no one’s first priority. To say it lingered in development hell would imply that any significant work was done towards putting it into production. The occasional press release implied it was in development, but no serious steps forward came until the 1960s.

Walt Disney Productions was a very different studio by then. From an independent cartoon producer, it had grown into a major studio with arms in live-action films, television, and of course, Disneyland. These ventures commanded most of Walt’s interest, enthusiasm, and hands-on involvement. The disappointments of the 40s lingered on for Walt, and he never fully recovered his passion for animation. His involvement with the feature cartoons of the 1950s was a downward trend, to the animators’ frustration, and as beloved as these films have become over the years, their reception at the time was hit and miss. On top of that, the cost of producing animated films kept rising. Things came to a head in 1959, when Sleeping Beauty cost $6 million, $56 million in today’s money. If that still doesn’t seem like much, consider that Sleeping Beauty was among the ten highest-grossing films of 1959, and still couldn’t recoup its production and marketing costs.

Against those stark figures, Walt’s older brother and business partner Roy O. Disney pressured him to shutter the animation department. There was no more need, he argued; they’d made enough cartoons that they could sustain that legacy through theatrical reissues. Walt refused, but he did concede to economics. Staff was reduced and the ink and paint department was replaced with a method for xeroxing drawings onto cels. If these concessions weren’t enough for Roy, then the critical and popular success of 101 Dalmatians secured the life of the animation department, at least in the short term.

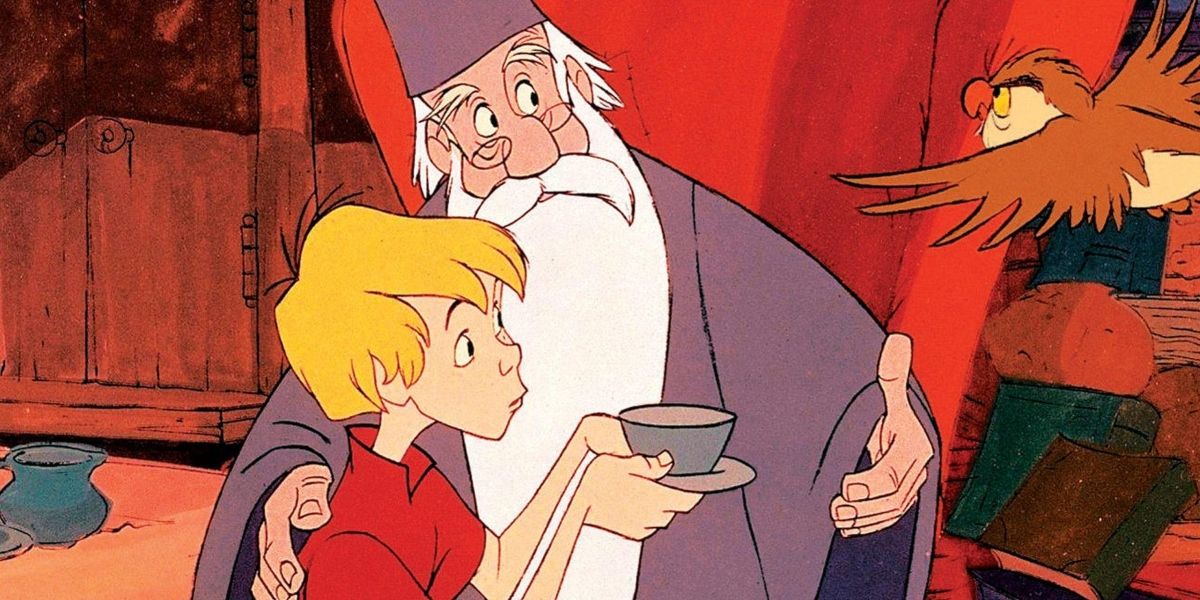

But Walt’s detachment from animation was probably at its strongest during this time. He had little involvement with 101 Dalmatians. The story development process was traditionally handled by a group of artists led or at least supervised by Walt himself. On Dalmatians, there was only one story man: Bill Peet, a Disney veteran of nearly 30 years. Peet single handedly storyboarded the entire film, and its success gave Peet an unusual amount of clout at a studio where everything operated on its namesake’s pleasure. Tasked with developing the next animated feature, Peet dusted off The Sword in the Stone. By that time, the rest of The Once and Future King had been published, and the shift in tone was obvious. There was even another adaptation extant: the musical Camelot, loosely derived from the last two books. Taking in a performance of Camelot helped convince Walt to greenlight The Sword in the Stone. But Peet shied away from White’s later, heavier material. “We decided to make it playful because almost everyone knows the story,” he said. “There had already been too many Knights of the Round Table epics and that was not for us.” Against common practice for animation at the time, Peet wrote out a screenplay before storyboarding the film, to help in “sorting and sifting” the novel into a direct storyline. Walt weighed in with a request for “more substance,” but his greatest contribution may have been without his knowledge or consent: Peet patterned the nose, the playfulness, and the temper of Merlin (the film does not use White’s spelling) after Walt himself, part of a trend among Disney animators of basing benevolent but ill-tempered authority figures on their boss; the wizard Yen Sid in Fantasia was made in Walt’s image as well).

By 1960, Peet had his script boarded and ready to move on. There was just one problem: the animators didn’t want it.

A group of them, led by animator Marc Davis and art director Ken Andersen, wanted to tackle another contemporary setting after Dalmatians, and thought that they had a vehicle in an updated and Americanized version of the French play Chantecler, about a Gallic rooster who thinks his crowing makes the sun rise. It was another project that dated back to the late 1930s, one that had been abandoned multiple times when the story failed to come together. But the animators promised Walt a fresh approach, and a team of six spent six months developing it. Peet was aware of Chantecler, but he didn’t share in the enthusiasm for it. “It’s just a little too weird,” he told the team. “They all got pretty angry with me.”

This wouldn’t have been a problem in years past; Disney had multiple animated projects in the works from the time of Snow White. But Roy’s pressure on Walt continued, and so did the need to cut costs. Walt stood firm in refusing to shut down animation, but he agreed to scale back production from a film every two years to every four. This meant that, of the two pictures he had lined up, only one could go forward, and no such decision happened at Disney by anyone except Walt. Peet and the Chantecler team would need to give a show-and-tell on the work they’d done.

Accounts vary on what happened next. Walt was notorious for slipping into offices at night to get an early look on work being done at the studio. He apparently did so with his competing animated projects, and came to the conclusion ahead of the pitch sessions that The Sword in the Stone was the film that would move forward. In the Marc Davis version of the story, Walt couldn’t bring himself to tell Davis and Andersen, two long and loyal employees he was very fond of, that he wasn’t advancing Chantecler. He let one of Roy’s workers derail the story pitch with a put-down, walked out without a word, and later offered Davis more rewarding work away from animation. In Bill Peet’s rather self-congratulatory account, Walt did have something to say in the Chantecler pitch: “Just one word – shit!” before leading everyone into Peet’s office to see The Sword in the Stone.

“Here come all of these people,” recalled Peet. “They were all sulking and hoping I’d fall on my face…when I was done, Walt asked them what they thought – pretty good, huh? And they said, ‘Oh yeah!’ You can imagine how humiliated they were to accept defeat and give in to Sword in the Stone…[Walt] allowed them to have their own way, and they let him down. They never understood that I wasn’t trying to compete with them, just trying to do what I wanted to work.”

But the decision may not have been as merit-based as Peet liked to suggest. His adaptation of The Sword in the Stone was more appealing to Walt’s sensibilities than Chantecler; Arthur, a bright-eyed youth saddled with the humiliating nickname “Wart” and bullied by his foster brother, was a more sympathetic lead than a pompous, delusional rooster. But Peet had also significantly pared back the number of characters from White’s novel. The fairies, Robin Hood, fantastic beasts, and multiple adventures in the animal kingdom were excised. Despite the remaining animal sequences and the magical battle between Merlin and Mim, most of the characters were humans with straightforward designs that wouldn’t be too challenging to animate. The musical numbers were few and unambitious in staging. What this all meant was that The Sword in the Stone was the less expensive option at a time when cost concerns were paramount.

The film still managed to cost almost as much as 101 Dalmatians, and while it made money at the box office, revenue was down, and reviews were mixed. Even within the studio, there were misgivings. Director Woolie Reitherman was reluctant to work on the picture from the beginning, songwriting team the Sherman brothers reflected that their songs were disconnected from the underscore and the narrative, and even Bill Peet admitted that the film hadn’t turned out as well as Dalmatians. But most of all, the underperformance of another feature cartoon had Walt worried, enough so that he wanted a much greater say in the next one after years of neglecting them. He had agreed to Bill Peet’s suggestion of The Jungle Book as the next animated film, and left Peet alone to develop it, but when he finally saw the first storyboard, he was not happy. “This wasn’t the first time Walt and [Peet] had clashed,” recalled story artist Floyd Norman, but it was the last. Peet left the studio, and his brooding take, more faithful to the Rudyard Kipling book, was supplanted by a light and breezy film that led with character, a direction set firmly by Walt. Biographer Bob Thomas wrote that Walt contributed to story sessions on the film with a zeal not seen since his earliest days working on Mickey Mouse shorts, and in the making-of documentary for The Jungle Book DVD, an animator recalled Walt saying in his last story meeting before his death: “Gee, guys, I had forgotten how much fun this is!”

As for The Sword in the Stone, it had its theatrical reissues and TV airings, and then its release to home video and streaming services. It still has its fans – when I told him I was writing this, my dad started looking for the DVD. And even the middle-tier Disney titles can’t escape the curse of the live-action remake. Announced in 2015, that project has yet to begin production. Given the track record of these remakes to date, one may reasonably expect another forgettable retread that might as well blow off to Bermuda. But there is always the chance, however slight, that an eccentric filmmaker can become attached, crack the code to a definitive Arthurian movie, and pave the way to that full and proper adaptation of The Once and Future King George R. R. Martin still hopes for.